- Home

- Krav Maga Blog

- Krav Instructors

- Train in Israel

- Tour Train Israel

- Krav Shop

- DVD

- Kickboxing

- IKI Near Me

- Seminars

- IKI Membership

- On-Line Training

- Krav Maga Training

- Testimonials

- History Krav Maga

- Instructors Page

- Past Blogs

- Spanish

- Italian

- Certification

- Contact

- Holland Seminar

- Vienna Seminar

- Poland Seminar

- Italy Seminar

- Belt Requirements

Ethics of the Fathers and Sons

By Moshe Katz

CEO

Israeli Krav International

January 15, 2018, Israel

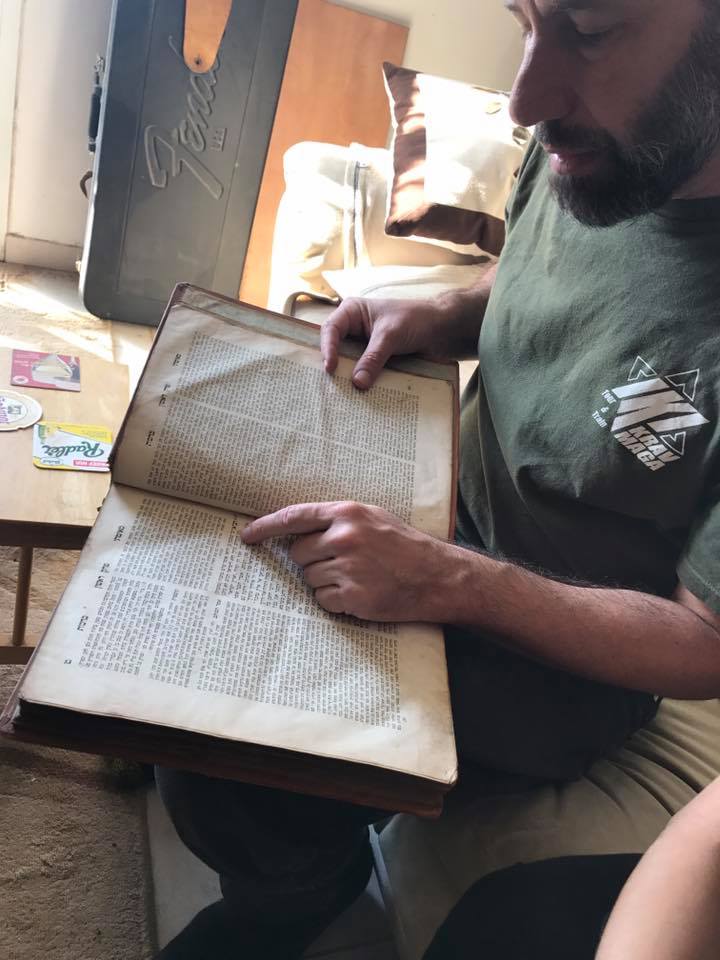

Studying a book composed two thousand years ago. This copy belonged to my grandfather Rabbi Isaac Klein of blessed memory. This copy was printed in Warsaw, Poland in the 1860's. It was one of few Jewish books to survive the Nazi persecution. First books were burned, and then people.

In Judaism we say "The actions of the Fathers are a sign for signs".

We say, "May your eyes always behold the sight of your teachers"

and we say, "One who has taught another is to be regarded as his father"

and we say "even if one only taught you one sentence you are to regard him and respect him as your teacher all the days of your life."

This is pretty powerful stuff. And it has shaped our lives, to this very day.

Words written thousands of years ago still shape our daily life.

And here is what is interesting. In Israel when I say "we" I do not only refer to the religious, to those who are committed to a way of life based on the Torah (Bible), I refer to all of us, for this has become part of our culture.

My Krav Maga instructor would not describe himself as religious by any stretch of the imagination and yet he always referred to my students as his grandchildren. The same is true of his teacher. These Biblical and Rabbinic values permeate our way of life and pepper our style of speech.

The Talmud is our book of law, customs and folklore. Each "Tractate" deals with a different part of Jewish law; commercial business, the laws of the Sabbath, the laws of the Passover festival, laws about food, the laws of marriage, of divorce etc. But there is one notable exception; the Ethics of the Fathers. This one little book does not really fit in. Something here is not like the others.

This is not a book of law and there are no regulations here that are binding in any legal way. It is a book about traditions and ethics, values.

It begins, "All of Israel have a share (a portion) in the world to come". Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch explains, "This denotes a two fold future, one in the world to come and one in this world."

What this means is that we all share in this world. We all share the same space and thus we want to make it a better place. When we speak of a "bad neighborhood" it is bad because we make it bad, we rob each other, and hurt each other. We all have the ability to create a "Good Neighborhood" by being good to each other.

We all have a share in the world to come and therefore we should all behave as this book describes, we should learn from the lives of the holy rabbis because it is to our benefit. We should look to our teachers as role models because we desire a better existence. We all have a share in this, we are all in this together. Few words but deeply profound. And these words go back at least 2,000 years.

The book begins

Moshe received the Torah from Sinai (i.e. from God on mount Sinai 3,700 years ago) and passed it on to Yehoshua; Yehoshua passed it on to the Elders who further passed it on to the Prophets, and the Prophets passed it on to the Men of the Great Assembly (an assembly of 120 scribes, sages, and prophets).

They said three things, be cautious in judgment, raise up many disciples and make a guardian fence to protect the observance of the law.

Now from here the Book (The Ethics) lists the Elder/Rabbi/Teacher or pair of leading authorities in each generation who were the guardians of the teachings, the transmitter of the tradition. And here is an amazing lesson.

With each generation the scholar or pair of scholars are listed. They are the receivers of the tradition, of the holy law, they have the honor of being the link in the chain and the ones to teach the next generation and to ensure that the flame of the Torah wisdom does not go out.

This was a major challenge. We are dealing with some pretty tough times; wars, the influence of Hellenism, The Roman empire, Christianity, the persecutions of each age. And yet these rabbis had to make sure the traditions, the teachings of previous generations did not die and were not lost to future generations. Keep in mind that this was all done orally for the most part.

At a certain point the rabbis felt a need to write down the teachings but again, keep in mind, this was done by hand. It was not until the mid 15th century that the printing press was invited. Transmitting the teachings was a challenging task.

But these men were not only transmitters, they were far more than that.

Come and Learn: The Ethics does not just list their names, although this in and of itself would be honor enough. No, there is more. For each scholar we hear their most famous teaching, their legacy. "Antignus of Socho received the teachings from Shimon the Righteous, he used to say; be not like servants who served their master in order to receive a reward but be like servants who serve the master not for the sake of a reward, and let the awe of heaven be upon you."

What we see here is that each "Transmitter" was also a contributor. He was not simply one who passed on the teachings, he expanded upon them, clarified, elucidated and expounded points. He had the daunting task of adapting laws to new circumstances, politically, culturally and technologically. Does electricity constitute fire? How much can one compromise his appearance in order to land a job among Gentiles? How does one blend modernity and tradition? What about medical advances, how do they fit in with Jewish law?

Each rabbi/teacher was also a contributor. We see here a critical point and lesson: We maintain an unbroken chain to the source, we acknowledge where it came from but we are not stagnant. No teacher breaks off, starts his own school and says "I am the creator, I invented this." No, you did not. You are not an orphan raised by wolves. You had parents, you had teachers and you must acknowledge this. You must always remember your parents and teachers.

When we mention our departed parents and teachers we say, "My father my teacher, of blessed memory", "My rabbi my teacher, of blessed memory". We never just say their name.

We acknowledge their contribution to our lives with respect. We know where we came from. We give credit where it is due. When a Talmudic rabbi makes a statement it will be, "Rabbi Levi said in the name of Rabbi Cohen". Never do we want to give the impression that we ourselves came up with this idea if in fact we learned it from our teacher. These are the ethics of the fathers and of the sons for each is honored by this tradition. When we quote our teachers we honor them and we ourselves are honored to be their students and to be trusted with these teachings. If you have been recognized as a teacher yourself it is even a greater honor to acknowledge that you are part of a chain that goes back to the source.

There is a mystical story of Moshe/Moses sitting with God on Mount Sinai, and God shows Moses a vision. He sees a man studying the Torah and expounding and clarifying the words. Moses is confused and asks, 'Who is this?' God replies, it is Rabbi Akiva (Akiva son of Yosef, עקיבא בן יוסף, born around the year 50, murdered by the Romas in the year 135) Moses feels a little bit left out until one of the disciples of Rabbi Akiva asks, "But Master, from whence do you know this to be the truth?' and Rabbi Akiva replies 'It is a teaching passed down from Moses himself'. Upon hearing this Moses smiled and was satisfied.

It is the ethics of the Fathers, and of the Sons, that has allowed our tradition to survive and thrive for so long. There is a profound lesson here.

May our eyes always behold our teachers.

Many of my teachers have passed from this lifetime but I can still see them; their gentle smiles, their penetrating glances, and their profound wisdom.

Rabbi Akiva

Rabbi Akiva son of Yosef is one of the most famous and honored rabbis of all time. He is quoted greatly throughout the Talmud and Jewish literature. He support General Shimon Bar Kochba in the Jewish revolt against Roman oppression and paid for it with his life.

When the Romans decreed that the Jewish people may no longer study the Torah, our ancient wisdom, Rabbi Akiva openly defied them. He died a painful death having been turtured in the most ruthless Roman manner.

Akiva was a poor shepeard but humble and modest. His wife Rachel encouged him to take up the study of Torah at the age of 40. Akiva saw the water that can shape a rock, by going over it again and again. He remarked that if the soft water can penetrate the rock then the Torah can penerate his head. By the time he was martyred he had 24,000 students and was regard as the leading scholar of his generation.

Rabbi Akiva taught that on one hand the Torah is the word of God and cannot be changed and yet at the same time Judaism must develop. He managed these ideas of Tradition and Change by expounding and understanding the Torah on a deeper level. Thus Moses was a bit confused when seeing this vision; Rabbi Akiva had delved deeper into the true meaning of the holy words. Indeed Akiva was a champion for progress. In particular his approach elevated the status of women.

Rabbi Akivas' death was personally ordered by the evil Roman ruler, the consul Quintus Tineius Rufus. As Akiva was being killed he recited, as every Jew must upon death, the shema, the declaration of faith. His soul departed this earth as he completed the verse. He was so calm that the Roman thought him a sorcerer.

The Sages taught: One time, after the Bar Kochba rebellion, the evil empire of Rome decreed that Israel may not engage in the study and practice of Torah. Pappos ben Yehuda came and found Rabbi Akiva, who was convening assemblies in public and engaging in Torah study. Pappos said to him: “Akiva, are you not afraid of the empire?”

Rabbi Akiva answered him: “I will relate a parable. To what can this be compared? It is like a fox walking along a riverbank when he sees fish gathering and fleeing from place to place. The fox said to them: ‘From what are you fleeing?’ They said to him: ‘We are fleeing from the nets that people cast upon us.’ The fox said to them: ‘Do you wish to come up onto dry land, and we will reside together just as my ancestors resided with your ancestors?’ The fish said to him: ‘You are the one of whom they say, he is the cleverest of animals? You are not clever; you are a fool. If we are afraid in the water, our natural habitat which gives us life, then in a habitat that causes our death, all the more so.’

The moral is: So too, we Jews, now that we sit and engage in Torah study about which it is written: “For that is your life, and the length of your days” (Deuteronomy 30:20), we fear the empire to this extent; if we proceed to sit idle from its study, as its abandonment is the habitat that causes our death, all the more so will we fear the empire.”

Like the blogs? Own the books, all blogs now available in "Footsteps from Judea", the collected blogs by Moshe Katz.

Visit our other site

Israeli Krav International.com